If you're reading this, chances are you've spent hours lost in a game. But have you ever stopped to ask the simple question: what actually makes something a game?

At first, the answer feels obvious: "A game is something we do for fun." Fair enough. But here's the problem: watching seven episodes of Friends in a row is fun too, and that's not a game. So the definition has to go deeper.

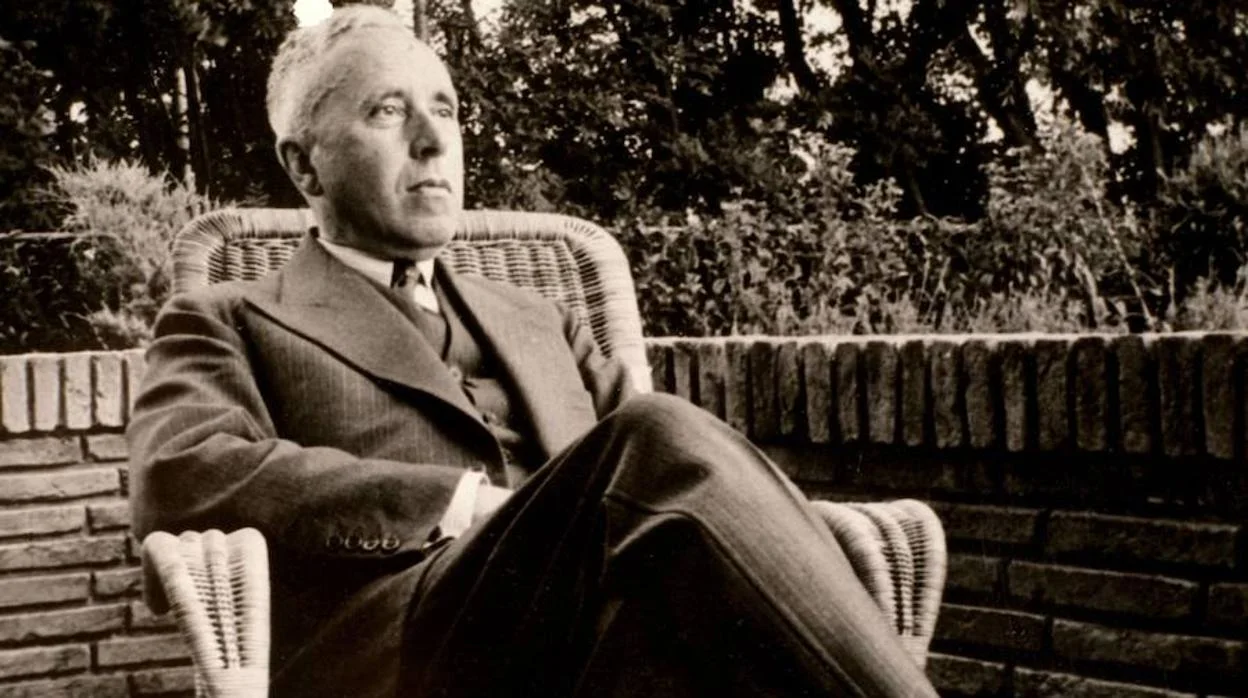

The First Big Attempt: Johan Huizinga

Back in 1938, historian Johan Huizinga published a book called Homo Ludens. He argued that games are:

- Voluntary: you can't be forced into play

- Separate from daily life: a little world of their own

- Uncertain: the outcome isn't fixed

- Unproductive: no material value is created

- Rule-based: everyone agrees to follow the same structure

- Make-believe: there's always a hint of pretending

In other words, games are a kind of magic circle we step into. Inside that circle, the normal rules of life are suspended, and new ones take over.

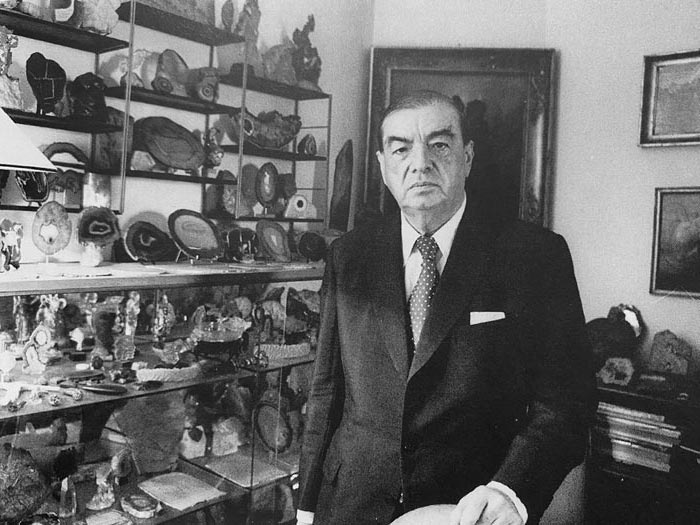

Leveling Up: Roger Caillois

Fast forward twenty years to 1958. Sociologist Roger Caillois thought Huizinga had a point, but he wanted to go further. He broke play into four categories we still use today:

- Agon: competition (sports, chess)

- Alea: chance (dice, roulette)

- Mimicry: role-play (theater, cosplay, make-believe)

- Ilinx: vertigo (spinning, roller coasters, thrill rides)

He also talked about a spectrum:

Paidia: free, chaotic play (kids running around, improv)

Ludus: structured, rule-heavy play (poker, soccer, chess)

Suddenly, we had language to describe why different games feel so different.

Wait, What About Esports?

Here's where it gets interesting. Huizinga said games don't involve material gain. But today, esports pros make a living playing League of Legends or Counter-Strike. Does that mean esports isn't play?

Not quite. The key is that the players aren't being paid simply for "playing." They're paid because they play exceptionally well in front of an audience. The game itself is still a game. The paycheck comes from performance, not the act of play itself.

The Modern Take: Salen & Zimmerman

Jump ahead to 2003. Game designers Katie Salen and Eric Zimmerman gave us one of the cleanest modern definitions in their book Rules of Play:

"A game is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome."

That definition hits home for digital games today:

- A system of rules and mechanics

- A conflict or challenge (not always violent, but always there)

- A measurable outcome (you win, lose, score, or progress)

It's less about whether a game is "serious" or "productive" and more about how the system creates meaningful play.

So… What's the Answer?

The truth is, there's no single perfect definition of "game."

Huizinga focused on the cultural role of play.

Caillois mapped out its forms and categories.

Modern designers highlight systems, rules, and outcomes.

Together, they remind us that games aren't just entertainment. They're frameworks that shape how we interact, compete, imagine, and even build culture.